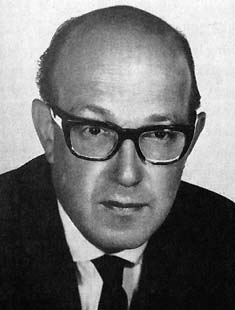

Witold Roman Lutosławski (January 25, 1913 –February 7, 1994) was a Polish composer and orchestral conductor, who was one of the major European composers of the 20th century, and one of the preeminent Polish musicians during his last three decades, earning many international awards and prizes with such compositions as four symphonies, a Concerto for Orchestra, a string quartet, instrumental works, concertos, and orchestral song cycles. Lutosławski’s parents were both born into the Polish landed nobility. Józef studied in Zürich, where in 1904 he met and married a fellow student, Maria Olszewska, returning to Warsaw in 1905. Witold, the youngest of three brothers, was born in Warsaw, Poland, on January 25, 1913, shortly before the outbreak of World War I. In 1915, with Russia at war with Germany, Prussian forces drove towards Warsaw. The Lutosławskis travelled east to Moscow, where Józef remained politically active. However, in 1917, the February Revolution forced the Tsar to abdicate, and the October Revolution started a new Soviet government that made peace with Germany. Józef’s activities were now in conflict with the Bolsheviks, who arrested him and his brother Marian. The brothers were interned in Butyrskaya prison in central Moscow, where Lutosławski—by then aged five—visited his father. Józef and Marian were executed by a firing squad in September 1918, some days before their scheduled trial.

After the war, the family returned to the newly independent Poland, only to find their estates ruined. After his father’s death, other members of the family played an important part in Lutoslawski’s early life, especially Józef’s half-brother Kazimierz Lutosławski, a priest and politician. Lutosławski started piano lessons in Warsaw for two years from the age of six. After the Polish-Soviet War the family left Warsaw to return to Drozdowo, but after a few years of running the estates with limited success, his mother returned to Warsaw. She worked as a physician, and translated books for children from English. In 1924 Lutosławski entered secondary school at Stefan Batory Gymnasium while continuing piano lessons. A performance of Karol Szymanowski’s Third Symphony deeply affected him. In 1925 he started violin lessons at the Warsaw Music School. In 1931 he enrolled at Warsaw University to study mathematics, and in 1932 he formally joined the composition classes at the Conservatory. His only composition teacher was Witold Maliszewski, a renowned Polish composer who had been a pupil of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. Lutosławski was given a strong grounding in musical structures, particularly movements in sonata form. In 1932 he gave up the violin, and in 1933 he discontinued his mathematics studies to concentrate on the piano and composition. As a student of Jerzy Lefeld, he gained a diploma for piano performance from the Conservatory in 1936, after presenting a virtuoso program including Schumann’s Toccata and Beethoven’s fourth piano concerto. His diploma for composition was awarded by the same institution in 1937.

Military service followed—Lutosławski was trained in signalling and radio operating in Zegrze near Warsaw. He completed his Symphonic Variations in 1939, and the work was premiered by the Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by Grzegorz Fitelberg, and this performance was broadcast on radio on March 9, 1939. Like most young Polish composers, Lutosławski wanted to continue his education in Paris. His plans for further musical study were dashed in September 1939, when Germany invaded western Poland and Russia invaded eastern Poland. Lutosławski was mobilized with the radio unit for the Kraków Army. He was soon captured by German soldiers, but he escaped while being marched to prison camp, and walked 250 miles back to Warsaw. Lutosławski’s brother was captured by Russian soldiers, and later died in a Siberian labor camp. To earn a living, Lutosławski joined the “Dana Ensemble,” a group of Polish revellers singing in “Ziemiańska Café,” as an arranger-pianist. Then he formed a piano duo with friend and fellow composer Andrzej Panufnik, and they performed together in Warsaw cafés. Their repertoire consisted of a wide range of music in their own arrangements, including the first incarnation of Lutosławski’s Paganini Variations, a highly original transcription of the 24th Caprice for solo violin by Niccolò Paganini. Defiantly, they even sometimes played Polish music (the Nazis banned Polish music in Poland—including Chopin), and composed Resistance songs. Listening in cafés was the only way in which the Poles of German-occupied Warsaw could hear live music; putting on concerts was impossible since the Germans occupying Poland prohibited any organized gatherings. In café Aria, where they played, Lutosławski met his future wife Maria Danuta Bogusławska, a sister of the writer Stanisław Dygat.

Lutosławski left Warsaw in July 1944 with his mother, merely a few days before the Warsaw Uprising, salvaging only a few scores and sketches—the rest of his music was lost during the complete destruction of the city by Germans after the fall of uprising, as were the family’s Drozdowo estates. Of the 200 or so arrangements that Lutosławski and Panufnik had worked on for their piano duo, only Lutosławski’s Paganini Variations survived. Lutosławski returned to the ruins of Warsaw after the Polish-Soviet treaty in April 1945. During the postwar years, Lutosławski worked on his first symphony—sketches of which he had salvaged from Warsaw—which he had started in 1941 and which was first performed in 1948, conducted by Fitelberg. To provide for his family, he also composed music that he termed functional, such as the Warsaw Suite (written to accompany a silent film depicting the city’s reconstruction), sets of Polish Carols, and the study pieces for piano, Melodie Ludowe (“Folk Melodies”). In 1945, Lutosławski was elected as secretary and treasurer of the newly constituted Union of Polish Composers (ZKP—Związek Kompozytorów Polskich). In 1946, he married Danuta Bogusławska. The marriage was a lasting one, and Danuta’s drafting skills were of great value to the composer: she became his copyist, and she solved some of the notational challenges of his later works.

In 1947, the Stalinist political climate led to the adoption and imposition by the ruling Polish United Workers’ Party of the tenets of Socialist realism, and the authorities’ condemnation of modern music which was deemed to be non-conformist. This artistic censorship, which ultimately came from Stalin personally, was to some degree prevalent over the whole Eastern bloc, and was reinforced by the 1948 Zhdanov decree. By 1948, the ZKP was taken over by musicians willing to follow the party line on musical matters, and Lutosławski resigned from the committee. He was implacably opposed to the ideas of Socialist realism. His First Symphony was proscribed as “formalist”, and he found himself shunned by the Soviet authorities, a situation that continued throughout the era of Khrushchev, Brezhnev, Andropov and Chernenko. Against this background, he was happy to compose pieces for which there was social need, but in 1954 this earned Lutosławski—much to the composer’s chagrin—the Prime Minister’s Prize for a set of children’s songs. It was his substantial and original Concerto for Orchestra of 1954 that established Lutosławski as an important composer of art music. The work, commissioned in 1950 by the conductor Witold Rowicki for the newly reconstituted Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra, earned the composer two state prizes in the following year.

The first performance of Lutoslawski’s Musique funèbre (in Polish, Muzyka żałobna, English Funereal Music or Music of Mourning) took place in 1958. It was written to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the death of Béla Bartók, but which took the composer four years to complete. This work brought international recognition, the annual ZKP prize and the International Rostrum of Composers prize in 1959. Lutosławski’s harmonic and contrapuntal thinking were developed in this work, and in the Five songs of 1956–57, as he introduced his twelve-note system, the fruits of many years of thought and experiment. He established another feature of his compositional technique, which became a Lutosławski signature, when he began introducing randomness into the exact synchronization of various parts of the musical ensemble in Jeux vénitiens (“Venetian games”). These harmonic and temporal techniques became part of every subsequent work, and integral to his style. In a departure from his usually serious compositions in 1957 to 1963, Lutosławski also composed light music under the pseudonym Derwid. Mostly waltzes, tangos, foxtrots and slow-foxtrots for voice and piano, these pieces are in the genre of Polish actors’ songs. Their place in Lutosławski’s output may be seen as less incongruous given his own performances of cabaret music during the war, and in the light of his relationship by marriage to the famous Polish cabaret singer Kalina Jędrusik (who was his wife’s sister-in-law).

In 1963, Lutosławski fulfilled a commission for the Music Biennale Zagreb, his Trois poèmes d’Henri Michaux for chorus and orchestra. It was the first work he had written for a commission from abroad, and brought him further international acclaim. It earned him a second State Prize for music. His String Quartet was first performed in Stockholm in 1965, followed the same year by the first performance of his orchestral song-cycle Paroles tissées. Shortly after this, Lutosławski started work on his Second Symphony, which had two premieres: Pierre Boulez conducted the second movement, Direct, in 1966, and when the first movement, Hésitant, was finished in 1967, the composer conducted a complete performance in Katowice. In 1968, the work earned Lutosławski first prize from the International Music Council’s International Rostrum of Composers, his third such award, which confirmed his growing international reputation. In 1967 Lutosławski was awarded the Sonning Award, Denmark’s highest musical honor. The Second Symphony, and Livre pour orchestre and the Cello Concerto which followed, were composed during a particularly traumatic period in Lutosławski’s life. His mother died in 1967, and in 1967–70 there was a great deal of unrest in Poland. Lutosławski did not support the Soviet regime, and these events have been postulated as reasons for the increase in antagonistic effects in his work, particularly the Cello Concerto of 1968–70 for Rostropovich and the Royal Philharmonic Society. At the work’s première with the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, Arthur Bliss presented Rostropovich with the Royal Philharmonic Society’s gold medal.

In 1973, Lutosławski attended a recital given by the baritone Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau with the pianist Sviatoslav Richter in Warsaw; he met the singer after the concert and this inspired him to write his extended orchestral song Les espaces du sommeil (“The spaces of sleep”). This work, Preludes and Fugue, Mi-Parti (a French expression that roughly translates as “divided into two equal but different parts”), Novelette, and a short piece for cello in honour of Paul Sacher’s seventieth birthday, occupied Lutosławski throughout the 1970s, while in the background he was working away at a projected third symphony and a concertante piece for the oboist Heinz Holliger. These latter pieces were proving difficult to complete as Lutosławski struggled to introduce greater fluency into his sound world and to reconcile tensions between the harmonic and melodic aspects of his style, and between foreground and background. The Double Concerto for oboe, harp and chamber orchestra—commissioned by Paul Sacher—was finally finished in 1980, and the Third Symphony in 1983. In 1977 he received the Order of the Builders of People’s Poland. In 1983 he received the Ernst von Siemens Music Prize. During this period, Poland was undergoing yet more upheaval. From 1981–89, Lutosławski refused all professional engagements in Poland as a gesture of solidarity with the artists’ boycott. He refused to enter the Culture Ministry to meet any of the ministers, and was careful not be photographed in their company. In 1983, as a gesture of support, he sent a recording of the first performance (in Chicago) of the Third Symphony to Gdańsk to be played to strikers in a local church. In 1983, he was awarded the Solidarity prize, of which Lutosławski was reported to be more proud than any other of his honours.

Through the mid-1980s, Lutosławski composed three pieces called Łańcuch (“Chain”), which refers to the way the music is constructed from contrasting strands which overlap like the links of a chain. Chain 2 was written for Anne-Sophie Mutter (commissioned by Paul Sacher), and for Mutter he also orchestrated his slightly earlier Partita for violin and piano, providing a new linking Interlude, so that when played together the Partita, Interlude and Chain 2 form his longest work. The Third Symphony earned Lutosławski the first Grawemeyer Prize from the University of Louisville, Kentucky, awarded in 1985. In 1987 Lutosławski was presented by Michael Tippett with the rarely awarded Royal Philharmonic Society’s Gold Medal during a concert in which Lutosławski conducted his Third Symphony; also that year a major celebration of his work was made at the Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival. In addition, he was awarded honorary doctorates at several universities worldwide, including Cambridge. Lutosławski was at this time writing his Piano Concerto for Krystian Zimerman, commissioned by the Salzburg Festival. His earliest plans to write a piano concerto dated from 1938; he was himself in his younger days a virtuoso pianist. It was a performance of this work and the Third Symphony at the Warsaw Autumn Festival in 1988 that marked the composer’s return to the conductor’s podium in Poland, after substantive talks had been arranged between the government and the opposition.

Lutosławski also, around 1990, worked on a fourth symphony and his orchestral song-cycle Chantefleurs et Chantefables for soprano. The latter was first performed at a Prom concert in London in 1991, and the Fourth Symphony in 1993 with the composer conducting the Los Angeles Philharmonic. In between, and after initial reluctance, Lutosławski took on the presidency of the newly reconstituted “Polish Cultural Council.” This had been set up after the reforms in 1989 in Poland brought about by the almost total support for Solidarity in the elections of that year, and the subsequent end of communist rule and the reinstatement of Poland as an independent republic rather than the communist state of the People’s Republic of Poland. He continued his busy schedule, travelling to the United States, England, Finland, Canada and Japan, and sketching a violin concerto, but by the first week of 1994 it was clear that cancer had taken hold, and after an operation the composer weakened quickly and died on February 7, 1994, in Warsaw at the age of eighty-one. He had, a few weeks before, been awarded Poland’s highest honor, the Order of the White Eagle (only the second person to receive this since the collapse of communism in Poland—the first had been Pope John Paul II). He was cremated; his devoted wife Danuta died shortly afterwards.

The following work by Witold Lutoslawski is contained in my collection:

Funeral Music.